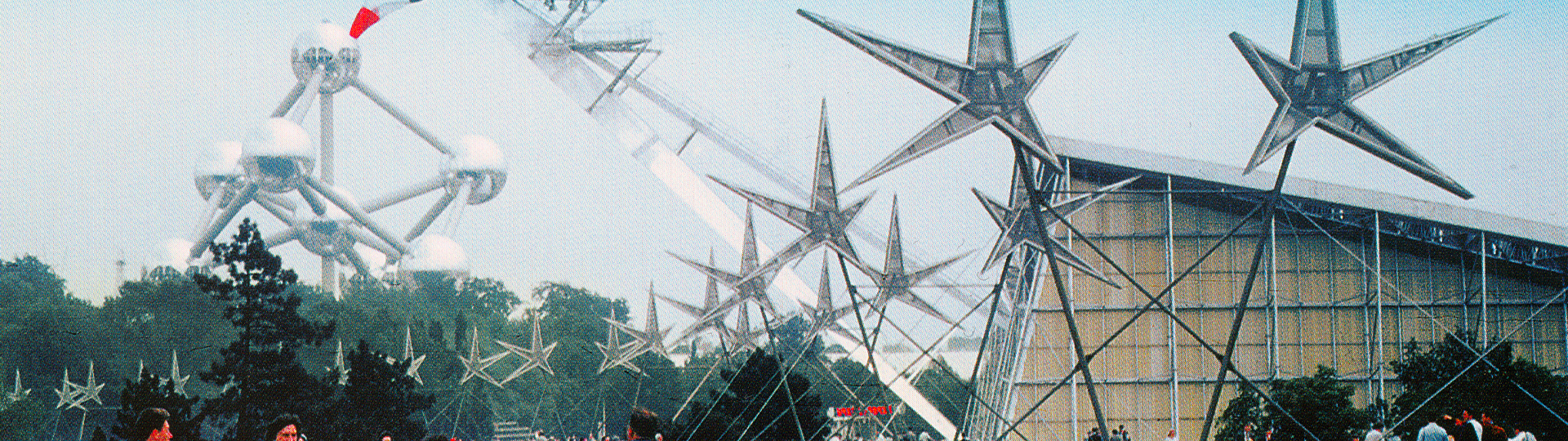

EXPO 58

On 17 April 1958, the Brussels World's Fair opened at the Heysel site. This large-scale event was a showcase of Belgium and 44 countries (at a time when the UN had 82 members). With the slogan, a world for a better life for mankind, this event propagated a message of limitless optimism and is a reflection of a society confident in its future and enthusiastic about the future of humanity.

THE GENESIS OF EXPO 58

In 1953, Brussels was designated to host the first World's Fair to be organised since the end of World War II. Competing against Paris and London, the Belgian capital convinced the jury because of Belgium’s unequalled experience in hosting World's Fairs: between 1885 and 1935, seven had been held on its soil.

The European economy was booming at that time. The Thirty-year post-war boom was characterised by a considerable rise in living standards of the European populations at a time that looked to the future with eternal confidence. The theme of Expo 58 was - a world for a better life for mankind where this new world of never-ending growth was based on faith in technical and scientific progress. Pure science would provide salvation for humanity, as one of the event's many exhibitions endeavoured to show.

THE TRANSFORMATION OF A CAPITAL

Opened to the public from April to October 1958, the World's Fair was an immense success: 41,454,412 admissions were recorded. Expo 58 provided a unique window on the world at a time when foreign travel was still rare. In order to host it, Brussels, recently named capital of the European Economic Community, was metamorphosed and adapted to the needs of the aeroplane and car, which were becoming increasingly popular, with urban motorways and a new airport at Zaventem in the suburbs of Brussels.

At the same time, housing developments meeting the most modern architectural standards were to spring from the earth, like the neighbouring Model City [Cité Modèle] of Laeken, coordinated by the Belgian architect Renaat Braem, a disciple and admirer of Le Corbusier. The initial programme was delayed considerably, and the Model City [Cité Modèle] was not fully completed until the 1960s.

SMILES ACROSS THE BOARD

Expo 58 was thus an exercise in modern communication for Belgium of the fifties that staged it. We witnessed a media hype that made the event unavoidable. Belgium wanted indelibly to impress Belgian and foreign visitors by demonstrating a lively and youthful image.

The posters and flyers from the time are a reflection of the hospitality, courtesy and promotion campaigns surrounding Expo 58 and that also reflect the graphic world of the nineteen fifties.

THE STAR LUCIEN DE ROECK

If Expo 58 marked hearts and minds, the same is true of its logo, the Star called Lucien De Roeck named after its designer, who became a design legend since then.

As a professional, Lucien De Roeck sought to bring together the elements suggest by this exhibition in a clear and simple single graphic element, above all taking account of its universality and the city in which it was located. He considered several options, including a tree stripped of its leaves, the branches bearing symbols characterising the exhibition.

But it was the theme of the Star that prevailed: I adapted the shape to a star that, in my opinion, could best explain the dynamism of this exhibition in the distorted shape I gave it. To this he added the notion of universality by using the globe and set it all in time and symbolically and paradoxically in eternity, with the figure 58 as these two figures alone mark the entire exhibition.

A WINDOW OF THE WORLD AND ON THE WORLD

With its national and commercial pavilions, Expo 58 literally presented a state of the world. Despite its message of peace and fraternity among nations, the great celebration of 58 was not spared Cold War tensions. At the foot of the Atomium, the Soviet Union (now Russia and the other Central European countries) and the United States of American mocked each other in a symbolic confrontation. Both attracted a curious and seduced crowd, the Soviet pavilion, with Sputnik at the centre, the first satellite in space, showcased the achievements of the communist society. Opposite, the American pavilion summarised the American Dream, consumer society and a certain comfort in life.

The most striking structures were those that emphasised the engineering exploits achieved in order to seek original solutions and techniques, such as buildings in prestressed concrete or hyperbolic paraboloid roofs. Among these exceptional pavilions, we should mention the Civil Engineering Arrow created by the engineer André Paduart, the architect Jean van Dooselaere, and the sculptor Jacques Moeschal; Le Corbusier’s Philips Pavilion; and the Marie Thumas restaurant pavilion, which was the work of a group of architects and engineers. With its emphasis on technical achievement, the Atomium fitted this context perfectly.

Other pavilions stressed the picturesque aspects of different countries and regions. There was a large - and somewhat controversial - colonial section testifying to Belgian rule in the Congo, at a time when the international context was evolving towards the end of European control of the colonies.

For its many visitors, Expo 58 remained a space for discovery, pleasure, and entertainment, in the image of a Belgique Joyeuse, a district of the Heysel, exclusively devoted to celebration.

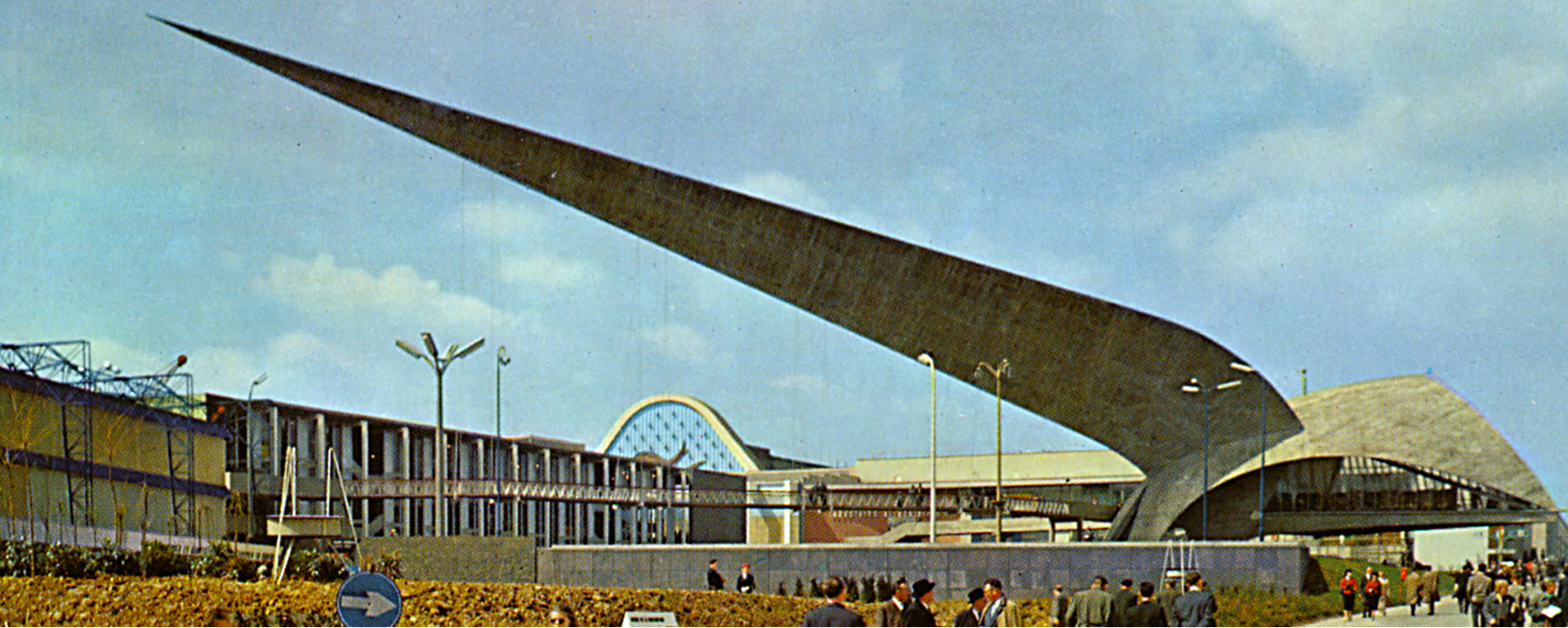

THE CIVIL ENGINEERING ARROW, THE OTHER TECHNICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL FEAT

Sometimes overshadowed by the fame of the Atomium, the Civil Engineering Arrow is nonetheless a feat of architecture, art and engineering, and it attracted much attention at the event.

Made of reinforced concrete, this immense, 80-metre long cantilevered structure was designed and built by the architect Jean Van Doosselaere, the engineer André Paduart and the sculptor Jacques Moeschal. In 1954, all three were commissioned to portray the victory of Belgian Civil Engineering over natural forces. After several attempts, they decided to create a construction in the form of an arrow. Work on this project began in 1957 and proved to be a real challenge. Firstly, the wooden framework was put in place; this was then covered with a thin concrete shell. A counterweight to the cantilevered beam was provided in the form of a triangular exhibition hall raised about 5 metres above the ground, featuring a glazed wall and a domed concrete roof. The entire structure stood on three legs, which ensured its stability. During its construction, the Arrow was supported by scaffolding; this was 72 metres long and 36 metres high and bore a weight of 450 tonnes. The construction supported a 58-metre long walkway, suspended 5 metres above the ground. This provided visitors with a bird’s eye view of a huge relief map of Belgium (scale: 1/3500), showing the country’s motorway network and major cities.

The Belgian Civil Engineering Arrow survived alongside the Atomium until the 1970s. In poor condition, it was demolished to make room for the car park of a commercial area.